Dirty Dublin

What is it?

What is it?

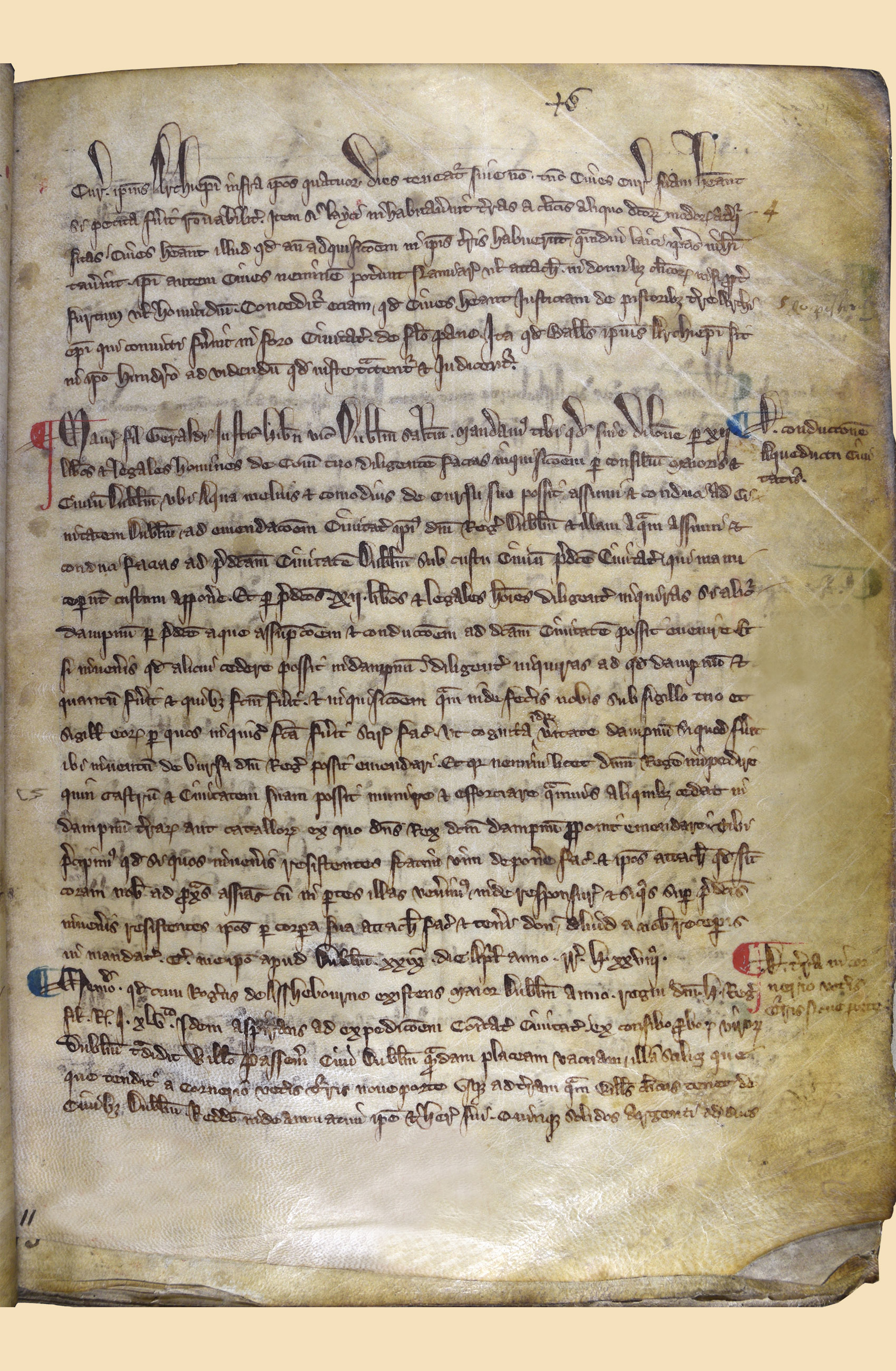

This is a royal order from a very annoyed King Henry VII sent to the citizens of Dublin in 1489.

Where is it?

Where is it?

You can see this manuscript in Pearse street Archive and Library, Dublin. It appears in one of the pages of The White Book of Dublin. It is called that because the pages are made from white vellum (calf-skin).

What does it say?

What does it say?

It demands the citizens of Dublin clean up their streets. Pigs were running everywhere and leaving dung behind. The filth was believed to cause sickness and ill-health. Apparently it was so bad people stopped visiting the city and some even died. The order also demanded beggars and homeless people leave the city too!

Read a translation

Read a translation

1489. November 14. Dublin

The King has been informed that dung-heaps, swine (pigs) and other nuisances fill the streets, lanes and suburbs of Dublin. They infect the air and produce mortality (death), fevers, and pestilence (sickness) throughout that city. Many citizens and visitors have thus died in Dublin. The fear of pestilence prevents the coming thither (to) of lords, ecclesiastics (priests) and lawyers. The King commands the Mayor and Bailiffs of Dublin to forthwith (immediately) remove all swine. To have the streets and lanes freed from ordure (poo!) so to prevent loss of life from dirty air. The Mayor is to make all Irish vagrants (beggars) and homeless leave the city.'

The King has been informed that dung-heaps, swine (pigs) and other nuisances fill the streets, lanes and suburbs of Dublin. They infect the air and produce mortality (death), fevers, and pestilence (sickness) throughout that city. Many citizens and visitors have thus died in Dublin. The fear of pestilence prevents the coming thither (to) of lords, ecclesiastics (priests) and lawyers. The King commands the Mayor and Bailiffs of Dublin to forthwith (immediately) remove all swine. To have the streets and lanes freed from ordure (poo!) so to prevent loss of life from dirty air. The Mayor is to make all Irish vagrants (beggars) and homeless leave the city.'

Is that how they spoke?

Is that how they spoke?

Yep! It’s old English. How we speak and write changes over time. Words like ‘pestilence’ and ‘thither’ are not used any more. Historians become familiar with old languages so they can understand these documents.

What type of source is this?

What type of source is this?

It’s a primary source because it dates from the time it was made (a secondary source dates after that time).

What is this evidence of?

What is this evidence of?

Go to the tasks tab and download Dirty Dublin Tasks to find out.

Football friends or foes

What is it?

What is it?

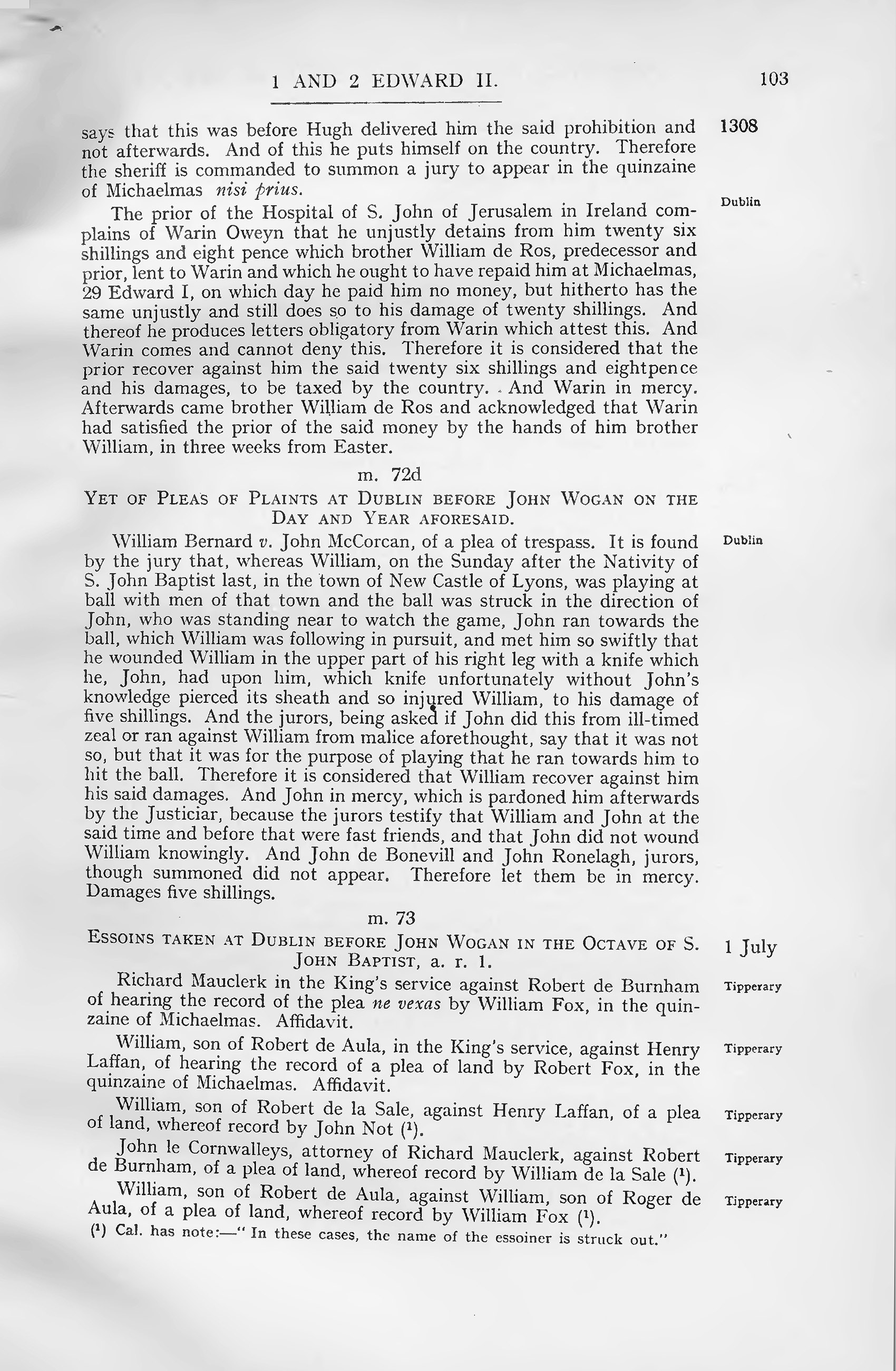

This is a legal court case that took place in Dublin on July 1st, 1308.

Where is it?

Where is it?

The original manuscript was destroyed during a fire in 1922. Luckily an historian had copied it before the fire and then published it in this book. You can read this and lots more court cases online via this link.

What does it say?

What does it say?

It is a report about two friends, William and John. They argued over an accident at a ball game in Newcastle Lyons, Co. Dublin. William was accidently stabbed in the leg by John during a tackle. John was carrying a knife but it had slipped through it's cover and injured William. They went to court but the jury decided it was an accident and there was no hard feelings.

Read a translation.

Read a translation.

‘Court Case report.

William B versus. John M.

It is found by the jury that, whereas William, in the town of New Castle of Lyons was playing at ball with men of that town. The ball was struck in the direction of John who was standing near watching the game. John ran towards the ball, which William was following. He met him swiftly (hard). He wounded William in the upper part of his right leg with a knife he had upon him. Without John's knowledge his knife had pierced it's sheath (knife cover). The cost of the injury was five shillings. The jurors asked if John did this with eagerness for the game or ran at William to hurt him. It was answered that it was for the purpose of playing that John ran towards William to hit the ball and not injure him. The jury heard that William and John, before the game were fast (close) friends and that John did not wound William knowingly’.

William B versus. John M.

It is found by the jury that, whereas William, in the town of New Castle of Lyons was playing at ball with men of that town. The ball was struck in the direction of John who was standing near watching the game. John ran towards the ball, which William was following. He met him swiftly (hard). He wounded William in the upper part of his right leg with a knife he had upon him. Without John's knowledge his knife had pierced it's sheath (knife cover). The cost of the injury was five shillings. The jurors asked if John did this with eagerness for the game or ran at William to hurt him. It was answered that it was for the purpose of playing that John ran towards William to hit the ball and not injure him. The jury heard that William and John, before the game were fast (close) friends and that John did not wound William knowingly’.

Is that how they wrote?

Is that how they wrote?

Sometimes. Legal documents like this use their own courtly language.

Is it a primary or secondary source?

Is it a primary or secondary source?

It’s a secondary source because the book dates after the time it was written.

What is this evidence of?

What is this evidence of?

Go to the tasks tab and download Football Friends Tasks to find out

The Guilty Archer

What is it?

What is it?

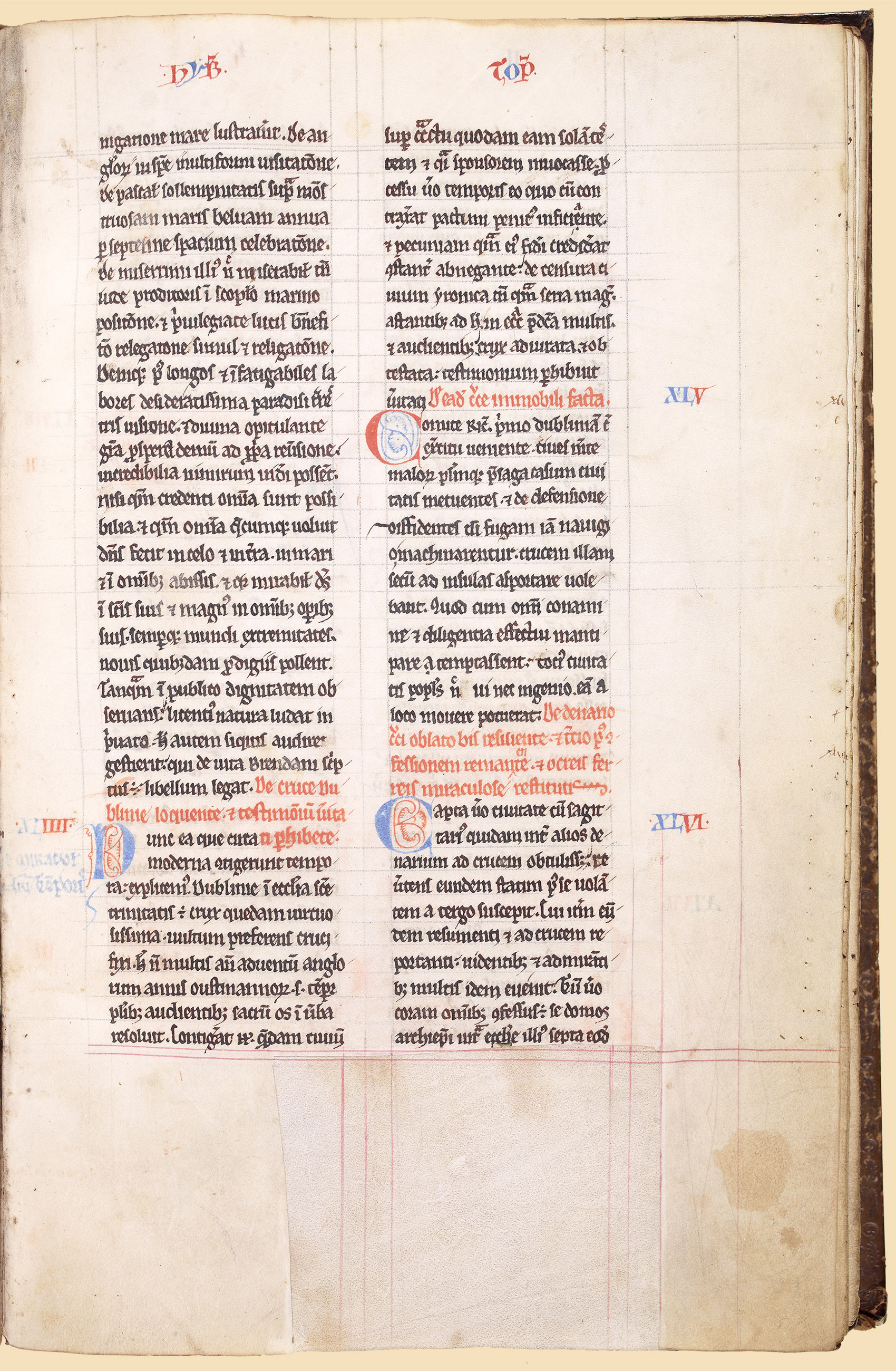

It is part of a travel diary with some curious stories written by a priest who travelled around Ireland in 1183AD.

What does it say?

What does it say?

It is the tale of an archer who broke into the bishop’s house in Dublin and stole from him. Afterwards, the archer tried to make an offering of money to a holy cross that stood in the middle of the town. However, the cross had magical powers and knew he had sinned. It made the money fly back at the archer until he confessed to his crime and returned what he had stolen.

Picture

Picture

A copy of this document can be found in London. The scribe who copied the story included this drawing. view image

Read a translation

Read a translation

A certain archer, among others, was offering a penny before the cross, when it flew back behind him.

Upon taking it up and again carrying it back to the cross it happened a second time to the surprise of many beholders (onlookers).

He then confessed, in the presence of the beholders that he had, that day, pillaged (raided) the bishop’s residence.

Upon this, being ordered by many beholders to give up the money, and restored (returned) everything he had pillaged.

He brought back the same penny for the third time with great fear and reverence, to the foot of the cross, where it remained.

Is this how they spoke?

Is this how they spoke?

Latin was written and spoken everyday by religious men. Most ordinary people could not write and they spoke Irish.

Is this source reliable?

Is this source reliable?

Historians must consider the writer of the source and if they might be biased. The writer in this case was a priest. He taught people about God and the punishments that would happen if people sinned. The writer included stories he heard and believed to help teach people how to be religious.

What is this evidence of?

What is this evidence of?

Go to the tasks tab and download The Guilty Archer Tasks to find out.

Artefact: Lamp

What is it?

What is it?

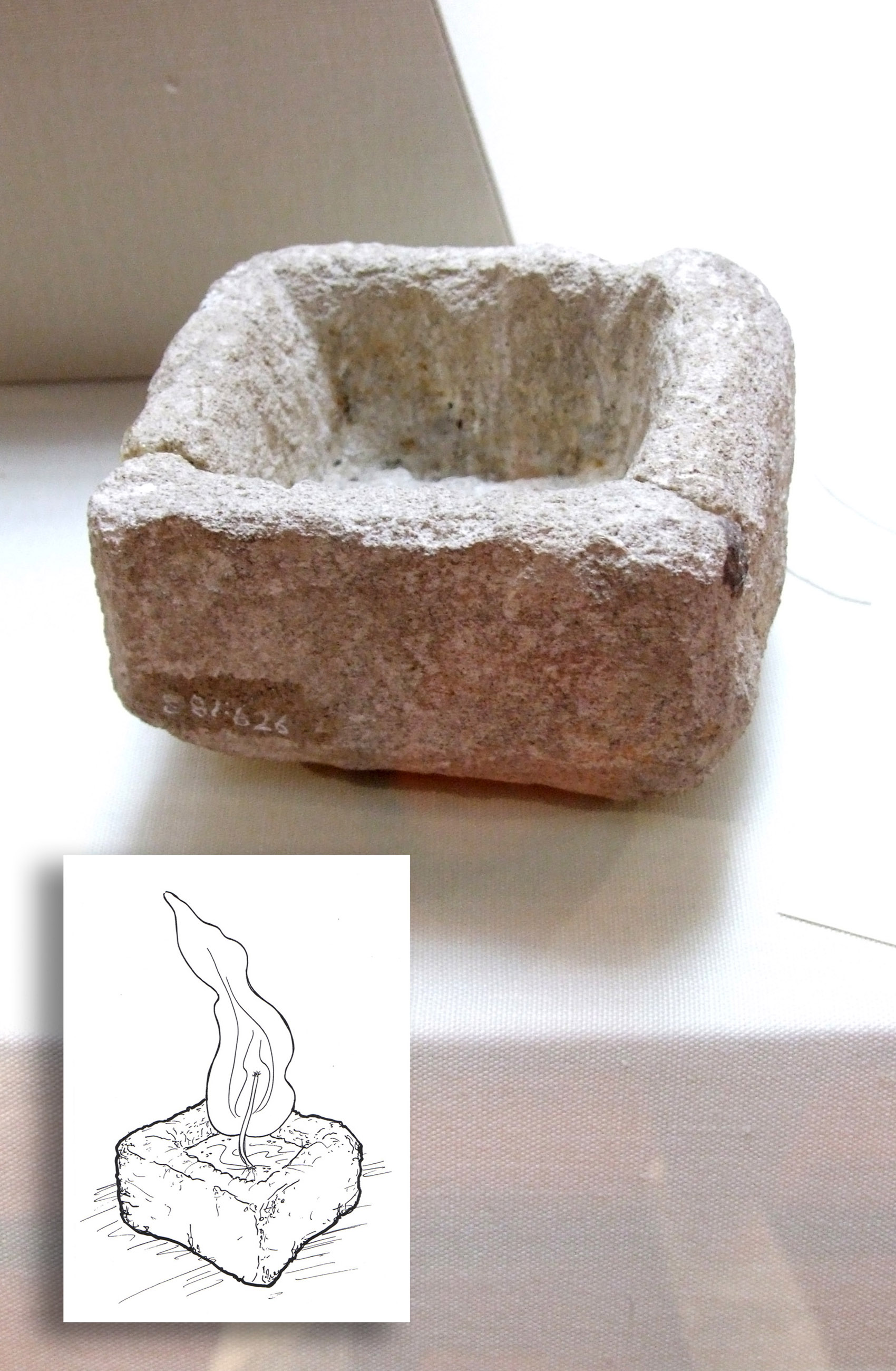

A medieval lamp. Archaeologists uncovered it during an excavation in Dublin along with lots of other fantastic medieval artefacts.

Where is it?

Where is it?

On display in Dublinia’s History Hunters exhibition.

It looks like a stone!

It looks like a stone!

Yes, it is made of stone. However, a hole has been cut into it by someone in the past therefore it is man-made. That’s how we know it’s an artefact.

How does it work?

How does it work?

The hole would have been filled with animal fat to make a candle. The wick was some dried moss. Medieval Dubliners used this to create light long before there was electricity.

What else do we know?

What else do we know?

Historians have told us lamps like these were often found in churches and in doorways. At night it was very dark without a lamp.

How do we preserve it?

How do we preserve it?

When archaeologists discovered the lamp it was broken in three pieces. Scientists called conservators at the National Museum of Ireland helped put it back together with a special glue. Now in Dublinia we keep it safe in a special glass case where visitors can see it.

Artefact: Wolf

What is it?

What is it?

A wolf skull found in Dublin.

Where is it?

Where is it?

On display in Dublinia’s History Hunters exhibition.

How did it die?

How did it die?

The skull belongs to an old wolf however, look carefully at the skull. To the right is a large hole. Archaeologists think the wolf was killed by a strong blow to the head.

Were there wolves in Dublin?

Were there wolves in Dublin?

Yes. They lived in the forests of Ireland and killed many people and livestock. They were scavengers too, known for eating up dead bodies left on a battlefield.

What happened to them?

What happened to them?

They became a big problem so were hunted till extinction. The last wolf to be seen was shot in Carlow in 1786.

Where can I see a real wolf?

Where can I see a real wolf?

Dublin Zoo. There are no wolves in Ireland anymore.

Artefact: Bell

What is it?

What is it?

A medieval hand bell

Where is it?

Where is it?

On display in Dublinia’s History Hunters exhibition.

Where was it found?

Where was it found?

Archaeologists found it, and other artefacts, on a rescue excavation in Dublin. Developers were building a hotel in the area but it was on top of the site an old medieval church graveyard.

How old is it?

How old is it?

Archaeologists dated it using typology. It’s a way of dating by type, e.g. a type of mobile phone you buy today looks different to types of phones you could buy 100 years ago. They think this bell is about 800 years old.

What was it for?

What was it for?

It was a medieval alarm clock. Bells were used to call people to prayer or mass. There were no clocks or watches in medieval Dublin so monks and priests rang bells from the tops of round towers to signify what time it was. The bells were also rung to warn people of danger.

A Mystery

A Mystery

The artefact was sent to the National Museum of Ireland when it was discovered. Conservators at the museum found bits of wood or straw packed inside the bell. We don’t know why it was there. What do you think?